I'm a 48 year old male, so it might surprise people that I am a Netmum. But Netmum I am, and I have always found their website invaluable for finding days out, places to go, child-friendly pubs, etc. But I didn't realise until the other day that there was a Netmums Blog. I've been particularly inspired this week by the Blogging as Therapy series they are currently running, which features some great bloggers writing about their ordeals with conditions such as post-natal depression, OCD and infertility.

Readers of my blog will know that I've been using it, amongst other things, to write about my depression. I find it's a great way of unburdening. I can put my thoughts "out there" and they are then parked for anyone to come along and read them, and interact with them if they wish. Sometimes that's a lot easier for the sufferer than to try and engage in conversation with real people.

The very process of ordering my random and chaotic thoughts in a (hopefully) coherent manner brings a degree of clarity and understanding to them. In my professional life, in systems engineering and systems thinking, we call this "action research" (e.g., Checkland and Scholes, "Soft Systems Methodology in Action", Wiley 1990), where the point of analysing a problem situation is not necessarily to find a solution, but to better understand the problem, and that understanding is gained from the journey we undertake in doing the analysis.

Outside work, I belong to two creative writing groups. I sometimes struggle to find inspiration for material to contribute to the groups. My counsellor is encouraging me to write. She understands how therapuetic it can be for me. I'm hoping I can combine the two and write about my depression in a more creative rather than factual way. Hopefully that will help me unlock some of the reasons why I am the way I am. With luck I can make it entertaining rather than self-indulgent. And if people can relate to it and it helps them and their loved ones, in some small way, to understand their suffering, then that will be a bonus.

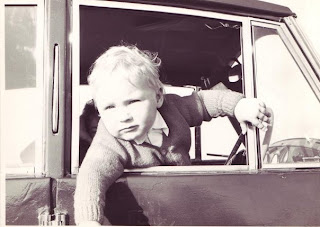

Watch this space then, but in the meantime, here's a short story I wrote back in January 2011. It's fiction, but of course there's a slice of autobiography in there. OK it's most of the cake rather than just a slice! The photos are from my own childhood and provided the inspiration for the story.

THE MONOCHROME BOY

“Right. Who wants an ice cream?”

“Me! Me!”, came the reply from the back of the Corsa in ear piercing stereo.

It was a warm, late summer’s day and Peter and the boys had parked up on the sea front, with the Common behind them. He could just make out the War Memorial in his rear view mirror and beyond that the faded splendour of the Queens Hotel. He hadn’t been here for years, but the previous night’s school reunion had made him nostalgic for the smell of fish and chips carried on the tangy sea air; for the sound of waves crashing on the stony beach then fizzing their way back down the steep shingle bank. He wanted to hear the ships’ horns sound as they passed through the narrow harbour mouth, the jangling and clanging of the penny arcades and the laughing sailor, which had scared the living daylights out of him as a boy, cackling at the entrance to Clarence Pier. He wanted candy floss. No, he wanted ice cream and he wanted Verrecchia’s ice cream.

Peter turned round to hand a fiver to his eldest son and dispatch him for the ice creams. He prided himself on having raised two children who were so vibrant and alive. They were brimming with that kind of unbounded excitement that boys their age have. The excitement that comes from every hour of every day being something new, an adventure, an undiscovered world that demands exploration. They had the confidence that being loved and being the centre of attention gives you. They enjoyed life, in exactly the naïve, innocent, trusting way that children should.

And they were close as a family, despite the obvious absence of a mother. They did father and son things together. The boys told him everything, delighted in sharing their excitement with him. He, in turn, treated them as his mates; more like little adults than children. He couldn’t have conceived of not taking them with him to the reunion the night before. That would have been as unnatural as not playing football with them, or not flying their kites on the common earlier. Peter’s old school friends had remarked on what a good job he’d done bringing them up, even if many of them had expressed themselves in rather surprised tones.

Just as Peter turned round, he was shocked to catch a glimpse of a third child in the back of the vehicle. This child couldn’t have been more different to his own two sons. This third boy was pudgy and languid, and staring forlornly into space. He wasn’t in a warm and sunny September day. He was peering, mole-like, to make out the Isle of Wight coastline throughthe steamed up windows and the clumps of chill February mist rolling in off the Solent. This child wasn’t off on an adventure to the magical kingdom of Verrecchia’s Ice Cream Parlour. Instead this child clutched a bottle of flat Coke, listlessly sucking the end of the straw into a soggy nub, disdainfully ignoring the unwanted bag of cheese and onion in his other hand. The third child didn’t have the latest Batman or Super Mario Bros cartoon exploding colourfully out of his T-shirt. He sat imprisoned and impoverished by the thin polyester shirt and a hand knitted tank top that had been such a boon for his classroom tormentors; bullies who had shaped, if not created, this solitary, withdrawn boy. He sported the ubiquitous cold sore – why did he always have a bloody cold sore? – that was so often mistaken for a glob of unwiped chocolate on his lip and which ruined many a school photo. This child was devoid of self-belief and vitality. He oozed sadness.

The third boy was in black and white, sitting in the back of a Ford Zephyr, only feet away from Peter, but trapped behind an impenetrable wall of deafening silence, separated by forty years of sorrow.

The third boy was in black and white, sitting in the back of a Ford Zephyr, only feet away from Peter, but trapped behind an impenetrable wall of deafening silence, separated by forty years of sorrow.

All he’d wanted to do was to get a bit closer to the hovercraft. He’d never even seen a hovercraft before, let alone been so close to one. All that separated him from this magnificent beached sea monster was a flimsy metal railing that surely could not contain the snorting beast. He screamed to his father to hold his hand and take him nearer, but he couldn’t be heard above the incredible roar of the engines, the air blasting sea water onto the coarse pebble beach and the cacophonous screeching of displaced seagulls. He wanted to get as close as he could; to feel the salty spray on his face, hear the pebbles ricochet off the barriers with the sound that the bullets made in the black and white westerns he watched on TV; to wave to the people trapped in the glass belly of this man made leviathan. But he wanted to do it with his hand clasped firmly in his father’s; to be able to hide in the folds of his father’s coat if the monster spat its lethal venom at him; to blanket himself in the security of his father, yet still experience the thrill of being so close up to danger.

How could his father have missed the point so badly when he’d shouted above the din: “Come on, let’s get you away from all this noise. The football results will be on the radio in a minute.” Why did his father not know what he wanted? Why did he always miss the point? Other kids’ dads got it. Why not his?

And to compound everything, his father bestowed on him the so-called treat that came the way of all seventies’ kids at the end of a family trip to the pub or the seaside: a bottle of Coke and a packet of crisps in the back of the car, to be enjoyed in silence, face trying desperately not to slump in disappointment.

Back in the warmth of the vehicle, away from the deadly pebbles and ferocious sea creatures, his mother’s ever present cigarette smoke billowed up a thick fog of fug between the boy and his parents. His mother and father, as was most often the case, sat in stony silence, with nothing to say to each other and no parental wisdom to impart to him. Just smoking and staring into space; a lifetime of smoking and staring.

The hovercraft’s noise had abated enough for the child to hear James Alexander Gordon intone, “Portsmouth one, Carlisle United” (and you could always tell from his inflexion that an away win was coming) “…four.”

“Bloody rubbish”, the boy’s father said for the umpteenth Saturday, and started the car. As the Zephyr jerked away, the Coke bottle banged sharply against the child’s front teeth, spilling the flat, brown liquid down his tank top, and another crushing childhood episode drew to a close.

Peter took the fiver back and opened his door. “Come on boys,” he said, “let’s do this together.”

As the three of them climbed out of the car and ran hungrily, hand in hand, towards the ice cream parlour, a modern, sleek looking hovercraft glided in near silence up the slipway, barely raising the noise level above that of the general promenade hubbub, almost hidden from sight by the recently installed safety screens.

At the same time, and yet forty years earlier, a monochrome boy in a black and white tank top looked out of a car window, cracked a cold sore smile in the knowledge that history wasn’t repeating itself, and split open a bag of crisps.

No comments:

Post a Comment